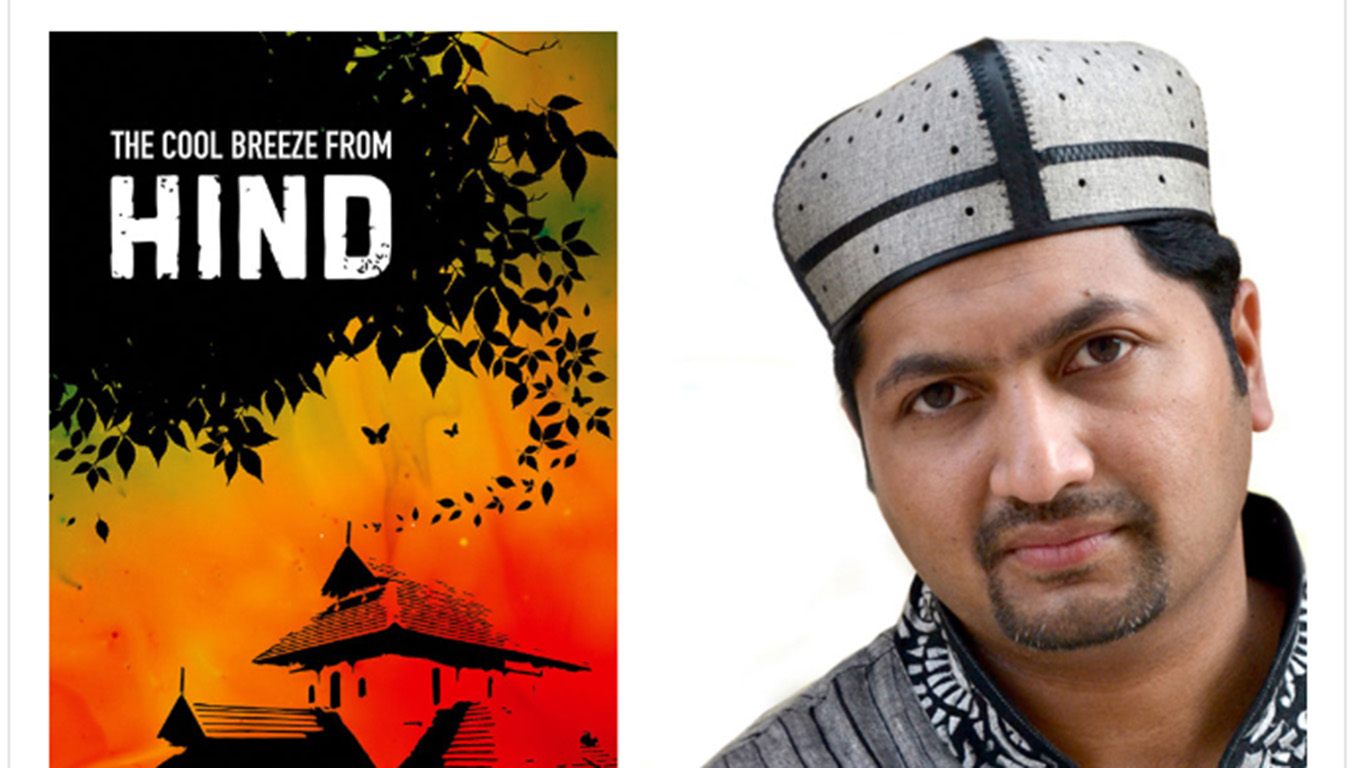

Book Review of Jaihoon’s The Cool Breeze From Hind by N. Muhammed Khaleel, published in the Companion.in, an online publication managed by a team of research scholars of leading Delhi-based Universities with the objective of creating a democratic and vibrant campus that brings forth a social change rooted in values and ethics.

Before the renaissance in English literature, there was racism in the representation of the subjects. In the works of French writer Andre Breton, he shows how this racism functions within the literary world. The lifestyles of the noble class, their complexities, romances and folk stories and of other elite classes dominated the central themes of the literature, whether fiction or non-fiction. Similarly, Malayalam too had such a dominance mainly of the Brahmanic. Even if Malayalee (the natives of Kerala) writers write in other languages, this dominance is often reflected. The lifestyle of elite class, especially of Brahmins, their everyday self-making, anxieties, tensions, dreams were the prevalent themes of the fiction and non-fiction. Even after the Renaissance in literature, this tendency lasted for a greater extent in English and Malayalam too. Hardly few writings cover the enigmas and life of the other classes. In this context, MujeebvJaihoon’s new novel ‘The Cool Breeze From Hind’ is a distinct work, which encompasses the everyday self-making of Malayalee Muslim, his religious life and forgotten emotions which remained unrepresented for long.

Even though ‘The Cool Breeze From Hind’ is a novel, it is also a recollection of the foreign-settled author’s memories hidden in the Kerala’s soil as he visits his homeland. One who reads the book can obviously understand that this work is not a mere nostalgia of an expatriate, rather it’s a surrealistic work where the author describes his astonishments, wonders and consternations to the Tasbih, the author’s spiritual comrade. Akin to the ‘The words (1923)’ by Pablo Neruda, he plays with the Tasbih, sharing his feelings and describeingvthe wonders of his homeland.

The only companion in his narration is Tasbih, whom the author describes as a rosary who helps to keep the remembrance of God. In his words, Tashib is a friend to escape from the sparkling darkness of modern world’s lure of materialism. The author attributes a high spirituality to Tasbih and once, while he was explaining about the national sentiments he reminds the Tasbih that ‘your ears are not to be used for this worldly noise’. However, he asks Tasbih to lend its ears to hear his story.

Starting from the birth of Islam in Kerala, it covers the historical contexts of the Faith in Kerala, the valiant freedom fighters like Kunjali Marakkar, Variyankunnath Ahmad Haji, their struggles, liturgies and the hagiographies of some Sufi saints, who lived in the bygone Kerala. At some junctures, he uses Tasbih to introspect and advice himself. ’Be fair and just, o comrade’. Through this advice to Tasbih, he is asking himself for Self-purification. Tasbih, to him, is a mentor, comrade and companion whom he assumes as spiritual guide just as Shamz Tabrez for Jalal al-dhin Rumi or Khidhr for Moses.

Nature and the forgotten past of the Malayalee

One of the most beautiful scenes of the rain is its aftereffects and is sometimes beautiful as rain itself. When the rain stops, new life forms develops, , old ones cease and the raindrops start dancing in the soil with a calm melody. Gem-like tiny droplets balance themselves on the leaves especially on chemb (colocasia) leaves, and shines when the sunlight falls upon it. For the lover, rain was a hope, for the poet, an inspiration and for the common man, a gift of god. Earlier the Malayalee could realize the aesthetics of rain and find joy in its rhythm. But the modern Malayalee forgot what the rain itself was. Living in the world of technology, his capability to enjoy has been lost. The author tries to collect this forgotten feeling of Malayalee and laments his indifference towards nature. He sarcastically mentions the aversion of malayalee towards rain.

‘what is so special about the rain that spoiled their plans?’

And the Malyalee wonders at the author’s wonder when enjoying the rain.

Hijaz, Hind and the Cool breeze

‘Only if I had a chance to see you once

To quench the thirst

If my beloved would come once

In delight my heart would rejoice’

Throughout the work, Jaihoon tries to bridge the culture of Hind (India) and Hijaz (Arabia), by taking reference from the historic relations of trade and non-trade affinities. He describes Hijaz as ‘Sand Dunes’ and Hind as ‘Paddy Fields’. Similarly, he calls the former as Nadu (land) of Maveli and the latter as Bilad (Arabic word which means land) of Hatim Tai. Further, he characterizes the letter sent from Hijaz to Hind as the link between Sand dune prosperity and Paddy Field poverty or the ties between Sand Dune bread-winner and Paddy Field bread-eater.

He also goes on to vehemently criticize the individualistic views of the people he met. He observes that when travelling in public bus it is hard to expect any fairness from the people. ‘Every time a new passenger came in, the driver smiled in and the rest of the passengers grinned’. ‘No mercy is shown by elders towards the little’. Thus author tries to demonstrate the individualistic mind of people in a sarcastic manner.

Mappila and the historical Malabar

The author has more or less succeeded in a critical portrayal of the Mapilas’ culture and history in the form of a historical fiction. His spiritual thoughts and Prophetic love were articulated in a fascinating matter. He intermittently deploys the slogans, poems and sayings from Manqoos Moulid (a prophetic Eulogy popular among conservative Malayalee households) about the prophetic love. On his historical inquest into Malabar, he traces the birth of Islam in Kerala to the travel of Cheraman king. Visiting the Prophet, the Indian Cheraman, the first person said to have travelled from India to see him, gifted him with a bottle of pickle made from Zanjabeel (ginger). This binding of Hijaz and Hind was based on his witnessing of the miracle of splitting the moons in the skies, performed by the Prophet in order to defend his Prophethood from the challenge of the the Quraysh (people of Mecca). His desire was to meet and embrace Prophet’s faith. By narrating the Cheraman’s story, the author also explicates his intense desire to reach near the prophet.

After the arrival of Islam in Kerala, it was guided by Makhdhums of Ponnani and later by the ulemas. In the era of colonialism in Kerala, several riots and massacres happened between the Muslim inhabitants and the colonial powers. Among them, the riot of 1921 was the most notorious one which frightened the British colonialists. Travelling through the land, the author recalls the valiant story of Khilafath movement, its leader Aali Musliyar, and their defiant acts against the British. While recollecting the old memories of Khilafath, he writes highly of his Mappila forefathers and their contribution to the independence of nation.

Aesthetics of Poetics

In the legacy of love, the author finds similarity of fragrance between Vilankoti (Umarqazi, a sufi saint cum poet, native of Veliyankode) and Sialkoti (Allama Iqbal, who lived in Sialkot). According to him language of love is one.

Vilankoti says,

‘For those in search of mercy

None so great than you in benevolence’

Sialkoti says,

‘Your mercy on the sinners is greater

In forgiveness it is like mother’s love’

Both Sialkoti and Vilankoti speak about the universality of love. But the foolish fellows, according to author, cannot understand the secret of this love.

The Cool Breeze

The cool breeze is the solace and relief for the author. It conditions his voice— granting him peace pleasure and acting as a fortune. It is the most wonderful sign of the God’s mercy on the creation. ‘When the cool breeze is around, no pain shall come from the wound’. The author reaches the extreme stage of surrealism when he describes the cool breeze as a guide, not as merely spiritual, but as mystical too. ‘We rub the cool breeze over our hearts to remove the dirt’.

In a nutshell, Mujeeb Jaihoon’s endeavor to portray the realistic picture of Kerala Muslims from past to present using the surrealistic mode of literature pays off well. Throughout the novel, he plays with the words in a rhythmic manner:paalam–kaalam, kaadu-paalakkadu and so on. However, the novel has a charming power of language and rendition with the powerful diction charged with the power of transcendence.

Published at https://thecompanion.in/book-review-a-modern-pursuit-of-the-mappila-identity/